How To Set The Right Price Every Time

Exactly how to price products is a big challenge for marketers, but new research provides valuable direction in this complex decision-making process.

It isn’t just “big picture” pricing, like establishing margins and an overall price point, that bedevils marketers. There is plenty of research that shows $499.30 is psychologically more distant from $500 than the minuscule real difference. Unfortunately, the advice from science is sometimes conflicting.

The Power of Precision

Multiple studies show that precise prices (involving odd numbers and decimals) are more believable. In Precise Pricing Pays Off, I describe research showing that both $4988 and $5012 caused subjects to estimate a higher real value for a product than for the same item priced at $5000.

Multiple studies show that precise prices (involving odd numbers and decimals) are more believable. In Precise Pricing Pays Off, I describe research showing that both $4988 and $5012 caused subjects to estimate a higher real value for a product than for the same item priced at $5000.

Following that guideline, a digital camera selling for $598.37 would appear to offer more value than a similar unit selling for $600.

Prices Have Syllables?

In conflict with this, however, is research showing that prices that are visually simpler seem lower. The effect, described in An Easy Way to Make Your Prices Seem Lower, was found to be related to the number of syllables in the price.

By conducting multiple experiments, the scientists found that we humans “sound out” prices in our mind (unconsciously, of course). More syllables translate into a higher perceived price.

So, one might ask, which is better? A simple, rounded price that seems lower or a precise price that implies more value?

New: The Rounded Price Effect

A new study by Singapore researchers Monica Wadhwa and Kuangjie Zhang helps resolve the dilemma, at least for certain kinds of products. (It also adds a new word to the marketing glossary, “roundedness.”)

What the researchers found was that the way the price was expressed “felt right” if it matched the way customers were thinking about the purchase. Rounded prices, like $100, matched purchasing decisions that were driven by emotion. Non-rounded prices, on the other hand, felt better when the purchase decision was a logical evaluation process (cognition).

The researchers give the example of a camera that is being purchased to take on a family vacation. The consumer is motivated more by feelings than cognition in this case, and a rounded price would feel right.

A camera being purchased to, say, take product photos for a business might benefit from a non-rounded price. In that case, the evaluation is likely to focus on features, specifications, price, and other rational factors.

Pricing psychology: Use round prices for emotional decisions, precise for rational. Share on XThe price formats that matched the decision process seemed to encourage staying in that mode. Positive feelings about the product were reinforced. The researchers referred to this as the rounded price effect.

It’s significant that the same product can be evaluated in different ways depending on the circumstances. One can’t make a blanket statement that, for example, electronics products should always use non-rounded pricing.

Why Does This Work?

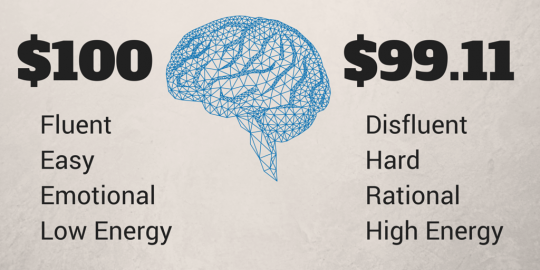

The researchers in the most recent study based their hypothesis on cognitive fluency. Rounded prices are easy for the brain to process, while odd prices make the brain work harder.

Emotional decision making is easy for the brain, while logical analysis is energy-intensive and tiring. (See Thinking, Fast and Slow for a review of Daniel Kahneman’s excellent book on the topic.)

So, a fluent rounded price keeps the customer in “easy” mode, while a less fluent, more complex price may add some friction and nudge the customer toward the harder work of cognition.

To Round or Not to Round?

The study focused on the frame of mind of the subject, and didn’t dig into the interaction of price and other marketing elements.

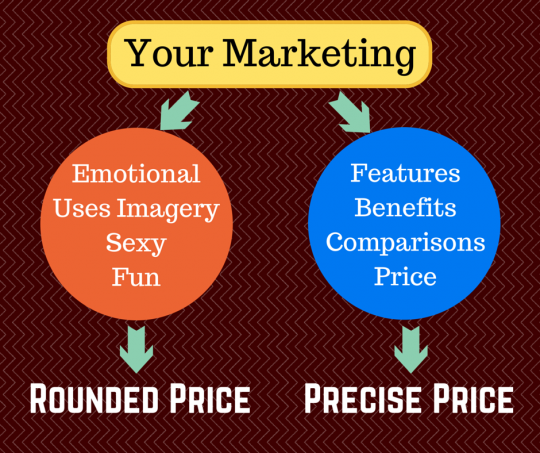

To me, that’s where the key takeaway lies. Instead of trying to guess how customers will be thinking, the marketer can influence the customer’s thought process by the way they present the product. Brands and businesses choose whether to use emotion, rational arguments, or a mix of both in their advertising. Depending on which path one chooses, the research suggests that the best approach to pricing is pre-determined.

If you are selling a camera based on its ability to capture and share family memories in a fun and easy way, a round price will keep the consumer in that emotion-driven mood and, most likely, get more sales.

Match your pricing style to the type of pitch you're making. Share on XIn contrast, if your marketing is built around the camera’s advanced specifications, large feature set, and competitive price, then a precise, non-rounded price should work better.

Luxury product purchases are usually driven more by emotion than facts, and hence would almost certainly benefit from rounded prices.

But wait…

Of course, a few caveats are necessary. First, many purchase decisions are driven by some combination of emotion (“I want it!”) and logic (“Does it do what I need?”). Different people will make the same purchase using different approaches and criteria.

The second caveat offers a partial solution to the first one. Every combination of market, product, customer, etc. is different. It’s risky to leap directly from lab results to the real world, and even from one set of real world results to a new situation. So, if at all possible, test the two pricing approaches.

A well-designed A/B test will not only show which pricing approach works best in your situation, but it may also reveal how your customers are actually evaluating your product.

Those insights, in turn, may help you refine your overall approach to marketing the product.