Deal or No Deal

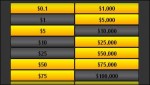

The wildly popular television game show, Deal or No Deal, is a televised neuroeconomics experiment (or would be if you could scan the brains of the participants as they played): each week, contestants choose to accept a fixed amount of money, or keep playing with the possibility of a still-higher payoff. In each round of the game, the payoff for stopping is based on the prize amounts remaining to be uncovered. I don’t watch the show, but on the few occasions that I’ve seen it I’ve noticed the different responses of the contestants (and their family members, who are often on camera as well). Some contestants amaze me by turning down a guaranteed six-figure payout to keep playing for a chance at a million dollars. Others bail out early to take the guaranteed cash. Family members are often at odds with the player, either exhorting the player to keep going if he’s wavering, or hollering at him to take the money and run if he’s turning down a big payout. Perhaps inspired by the game show, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have conducted an experiment that sheds light on the different ways people view rewards, risk, and time. Subjects were offered an immediate reward that might range from a mere ten cents to $105, or the alternative of a sure $100 payout that might be made in week or in up to five years.

The wildly popular television game show, Deal or No Deal, is a televised neuroeconomics experiment (or would be if you could scan the brains of the participants as they played): each week, contestants choose to accept a fixed amount of money, or keep playing with the possibility of a still-higher payoff. In each round of the game, the payoff for stopping is based on the prize amounts remaining to be uncovered. I don’t watch the show, but on the few occasions that I’ve seen it I’ve noticed the different responses of the contestants (and their family members, who are often on camera as well). Some contestants amaze me by turning down a guaranteed six-figure payout to keep playing for a chance at a million dollars. Others bail out early to take the guaranteed cash. Family members are often at odds with the player, either exhorting the player to keep going if he’s wavering, or hollering at him to take the money and run if he’s turning down a big payout. Perhaps inspired by the game show, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have conducted an experiment that sheds light on the different ways people view rewards, risk, and time. Subjects were offered an immediate reward that might range from a mere ten cents to $105, or the alternative of a sure $100 payout that might be made in week or in up to five years.

Not only do people differ in their preferences for immediate over delayed rewards of larger value, say the researchers in the Journal of Neuroscience, but these individual traits are mirrored by the level of activity in the ventral striatum, a key part of the brain?s circuitry involved in mediating behavioral responses and physiological states associated with reward and pleasure. Research volunteers classified as more impulsive decision makers, who tend to seek rewards in the here and now, had significantly more activity in the ventral striatum.

As reported by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Deal or No Deal? Need for Immediate Rewards Linked to More Active Brain Region, differences in “delay discounting” could be related to serious issues like addiction; individuals who choose immediate gratification in a neuroeconomics experiment may at greater risk for addiction.

“The ventral striatum appears to be a nexus where we balance acting impulsively to achieve instant gratification and making prudent choices that may delay rewards. Understanding what drives individual differences in ventral striatal sensitivity could aid efforts to treat people who have difficulty controlling impulsive behavior, by adjusting the circuitry,” explained lead author, Ahmad R. Hariri, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and director of the Developmental Imaging Genetics Program at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic.

Additional research will be directed at establishing that link. One issue I have with the current research is that the future payout may have been too low to predict an irrational choice. While I’m perfectly capable of understanding that the present value of a certain $100 payout in an average, say, of 2.5 years is likely to be higher than an immediate payout of some amount between a dime and $105, I’d probably take my chances on the immediate payout. So much for B-school. But why would I take the cheaper but immediate deal? I think in my case it has less to do with immediate gratification and more with mental overheard. Will I even remember in five years that someone owes me a hundred bucks? Will they find me? Will they be around to pay it out? For me, the computation would change completely if the future option was to hand me a savings bond that would mature on the future date. There’s still a bit of mental overheard involved – I’d have to put it someplace where it wouldn’t get lost, and I’d have to remember to cash it in – but a lot less than if I didn’t have it in my possession. I think if you repeated the same experiment for much higher stakes – say, a million dollars to be paid out in a week to five years, vs. $1,000 to $1,050,000 to be paid immediately, almost every subject would take the delayed but certain payout. I doubt if Pitt’s research budget will let them perform this test, but I’ll be happy to volunteer as a subject should they get funded. 🙂

Selling to the ventral striatum? There’s a neuromarketing lesson in this research as well: people are hardwired to respond in different ways to the same offer. Many types of product and service offers have these same elements as variables: immediate access to a product, shorter or longer payment terms, down payment or no money down, etc. Many product offers exploit the appeal of instant gratification with later financial consequences – think of those consumer electronics, furniture, and appliance offers that lead with, “No money down, and no payments until next year!”

The Pitt research and other studies show that beyond whatever practical financial considerations exist, different people’s brains will respond in different ways to an offer. From a practical standpoint, a “no money down” offer will appeal to buyers who don’t have enough money to buy a product outright or even make a down payment. But, it might well appeal to a consumer who has the ability to make a down payment but whose brain weighs the immediate use of the product against payments months in the future and finds the deal attractive. Conversely, some consumers with less need for instant gratification and more of an emphasis on future costs may find these deals unattractive, as they assume that financing costs will be hidden in the product’s price. So, to the extent possible, marketers should try to appeal to different purchaser brains. The auto industry is quite good at this with some of their offers – ads often give the buyer a choice between zero percent financing for the whole purchase, immediate cash back, and perhaps an attractive lease rate. Those ads create a sense of immediacy (the deals always have an expiration date), and have options to appeal to a variety of practical financial situations as well as a variety of less-rational analysis of the payment trade-offs.