Thinking About Money

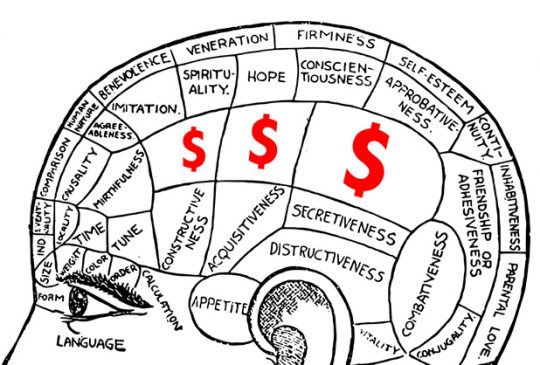

Earlier this year, we wrote Priming the Customer, which briefly covered some fascinating research in the area of priming. The concept of priming is simple, although it’s also a bit startling: by presenting an individual with subtle cues, one can affect subsequent behavior of that individual, entirely without conscious awareness of either the priming or behavioral changes. Now, as described by Greg Miller of ScienceNow in Money and Me, Me, Me, a study by psychologist Kathleen Vohs shows that supplying subjects with cues related to money can increase selfish behavior:

To examine this idea in a more controlled setting, Vohs, now at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and colleagues recruited several hundred college students to participate in a variety of experiments. In each experiment, the researchers subtly prompted half the volunteers to think of money–by having them read an essay that mentioned money, for example, or seating them facing a poster depicting different types of currency–before putting them in a social situation. In one experiment, the researchers gave volunteers a difficult puzzle and told them to ask for help at any time. People who had been reminded of money waited nearly 70% longer to seek help than those who hadn’t. People cued to think of money also spent only half as much time, on average, assisting another person who asked for their help with a word problem and picked up fewer pencils for someone who’d dropped them.

The antisocial behavior didn’t end there. Volunteers reminded of money preferred working alone even if sharing the task with a co-worker resulted in substantially less work. They also chose solitary leisure activities on a questionnaire–preferring a private cooking lesson, for instance, over a dinner for four. And when asked to set up two chairs for a get-to-know-you chat with another volunteer, subjects who’d seen a money-themed computer screensaver placed the chairs further apart than subjects who’d seen a fish screensaver, Vohs and colleagues report in tomorrow’s issue of Science. Taken together, Vohs says, the findings suggest that thinking of money puts people in a frame of mind in which they don’t want to depend on others and don’t want others to depend on them.

This work has interesting implications for advertisers, who frequently use money themes in their advertising. Big savings, higher investment returns, visions of prosperous retirement, money containers ranging from piggy banks to gleaming bank vaults… ads are full of them. Most of these ads appeal to the selfish interest of the viewer, so any priming that takes place matches the intent of the advertisement. An mutual fund company touting superior returns and prosperous-looking retirees clearly wants to appeal to the self-interest of the customer; they hope the viewer will indeed be enticed by these images to transfer funds to them.

Money-related advertising images are pervasive, though, and not all appeal to selfish interests. We’re currently in the holiday gift season, and the majority of print, television, and even in-store ads seem to emphasize savings. Are “save money on gift” advertisers shooting themselves in the foot by subtly priming the would-be gift-givers with selfish feelings? I don’t think so, in most cases – Christmas gifts are going to be purchased, and gift givers are going to check off their list of recipients with precision. A gift buyer who has to purchase gifts for six nieces and nephews isn’t apt to say, “Hmmm, this year I’ll just skip those ingrates.” Since the purchases are pre-ordained, appealing to the buyer’s self interest and offering substantial savings is a winning strategy.

The advertisers who might want to be cautious about money cues are those who are offers are appealing to the viewer’s feelings about others. Filling a viewer with feelings of warmth and a desire to please someone else and then reminding him about money could be self-defeating. Really, of course, it’s a tradeoff. Good salespeople often make the sale using feelings and emotion, and then close the deal with a financial incentive that has an expiration looming. (If you’ve ever sat through a time-share sales pitch, you’ll recognize that technique. Much of the focus is on warm & fuzzy feelings about recreation, quality time with family and friends, etc… but there’s always a financial incentive. Special financing is available only today, there’s a price reduction for 48 hours, and so on. This approach is clearly effective.) Each advertiser must make a judgment call on whether and how to bring money into the picture if the appeal is primarily an emotional one.

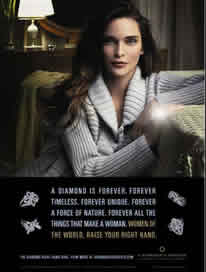

Think about the long-running A Diamond is Forever campaign – this is a good example of advertising that scrupulously avoids introducing money cues. Their ads are targeted at the luxury gift market. Spending large sums of money to give someone else a polished piece of carbon whose value is determined by cartel-enforced scarcity is hardly a concept that appeals to one’s self interest (unless, perhaps, you are Kobe Bryant trying to patch things up with an angry spouse). This effective ad campaign is a purely emotional pitch that would be spoiled by a tag line that offered, for example, “special savings in December!” The ads even avoid talking about the investment value of diamonds. Since these ads are run by the Diamond Trading Company, not retailers or manufacturers, injecting price would be difficult anyway; nevertheless, it’s a good example of a campaign that wouldn’t be helped if money entered the picture.

Think about the long-running A Diamond is Forever campaign – this is a good example of advertising that scrupulously avoids introducing money cues. Their ads are targeted at the luxury gift market. Spending large sums of money to give someone else a polished piece of carbon whose value is determined by cartel-enforced scarcity is hardly a concept that appeals to one’s self interest (unless, perhaps, you are Kobe Bryant trying to patch things up with an angry spouse). This effective ad campaign is a purely emotional pitch that would be spoiled by a tag line that offered, for example, “special savings in December!” The ads even avoid talking about the investment value of diamonds. Since these ads are run by the Diamond Trading Company, not retailers or manufacturers, injecting price would be difficult anyway; nevertheless, it’s a good example of a campaign that wouldn’t be helped if money entered the picture.

Because of the general congruence between money images in advertising and the self-interest of viewers, I don’t think these findings dictate changes in most ad campaigns. For campaigns that are geared to giving – special gifts, non-profit appeals, etc. – advertisers may want to be a bit cautious, and weigh the advantages and disadvantages of introducing financial imagery.

That’s really incredible! That’s why wealthy people are less althruist than the poors. Great article! =)