Power of Ten: The Weird Psychology of Rankings

Headline writers have known for years that rankings articles like “Top 10” lists generate clicks. University administrators have simultaneously dismissed USNews college rankings as inaccurate and irrelevant while still striving to improve their school’s own ranking. Practically everything is ranked these days – best cities to find love, best places to retire… people seem to love rankings, even when the rankings are so subjective as to be almost meaningless. Now, there’s some hard data that shows how we humans view rankings, and why it may be worth trying to move up (even if you think the rankings are bogus).

Headline writers have known for years that rankings articles like “Top 10” lists generate clicks. University administrators have simultaneously dismissed USNews college rankings as inaccurate and irrelevant while still striving to improve their school’s own ranking. Practically everything is ranked these days – best cities to find love, best places to retire… people seem to love rankings, even when the rankings are so subjective as to be almost meaningless. Now, there’s some hard data that shows how we humans view rankings, and why it may be worth trying to move up (even if you think the rankings are bogus).

A new study published in the Journal of Consumer Research looked at how people view ranked lists, and in particular the differences in perception of specific numeric rankings. (See: The Top-Ten Effect: Consumers’ Subjective Categorization of Ranked Lists.)

One digit to rule them all: zero

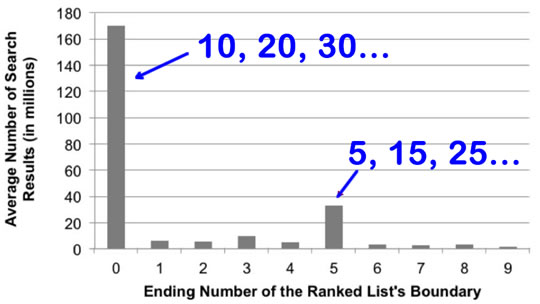

One of the first things the scientists looked at was the distribution of “top lists” found in Google. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority of lists they found ended in zero, with five being a distant second. The theory behind these round-number category groupings is that our brains try to categorize assortments of items into groups, and a “top ten,” for example, is an easy to visualize chunk. The distribution is striking, even if somewhat expected:

One of the most significant findings from the study is that if you fall just beyond the border of a category, your perception is lower than an even distribution of preference would suggest. Apparently, just missing the top 10 means that you are part of the next tier. And, you pay the price for not making the cut.

It’s not easy being green. Or #11.

There are a couple of lessons here for marketers. First, if your product or service is being ranked, it’s a lot better to be the last one in the higher-rated group (ending in zero) than the first one in the next group. Even though the differences between those positions may be inconsequential in real terms, the perceived difference in the eye of the consumer will be greater. The scientists, looking at hypothetical rankings of math students, found that the biggest perceived gap in student quality was between #10 and #11. The fact that this gap exceeded that between other ranking positions, like #9 and #10, was due solely to ranking bias, not any objective data about the students.

This was born out by an analysis of real-world business school application choices, which showed that schools moving into the next category up (say, top ten) saw a bigger increase in applicant interest than schools whose rankings improved by the same amount but who did not change categories.

This research simultaneously highlights the biases and false perceptions created by rankings and shows why it’s important to improve your ranking, particularly if you fall just outside a higher numeric grouping. Maybe those college administrators who complain about rankings but also try to game the numbers to boost their school’s rank have the right idea after all…

Content Marketing with Lists

Content marketers often use “top lists” or rankings as content that will be viewed and shared. These ranked lists are well established as both “linkbait” and “clickbait.” While the study doesn’t show that odd numbered lists (e.g., “12 Best Destinations…”) will be less appealing, it does seem that our brains like numbers that can easily be chunked into groups. So, a list of 20 can be easily divided into the top ten and second ten. It would be an interesting test to compare the click rate and/or sharing rate of an even-numbered list (10 or 20) vs. a more unusual number (14 or 19). I’m inclined to think that the even-boundary list would get more clicks and shares, but it’s possible the more unusual counts might get attention simply because they are unexpected. How often does one encounter a Top 17 list, for example?

And, if you happen to be one of those ethical list creators who wants to avoid ranking bias, one study showed that if the list was an odd number like 19, the category border effect is greatly reduced or eliminated. So, in addition to the caution that “closely ranked products don’t differ significantly,” further reduce reader bias by using an uneven cutoff for the rankings.

Rankings Are Here to Stay

One thing seems certain. Even though many, if not most, rankings are highly subjective and probably misleading to readers, they seem to fit a need in our psyches. When we’re faced with a choice of hundreds of potential colleges, for example, we want to know things like, “which are best, and is School A better than School B?” Secondary rankings, like “the top engineering schools” and “biggest party schools” may also come into play. Even when we acknowledge to ourselves that one can’t determine a “best” college without knowing a lot about the student’s interests, abilities, personality, and so on, rankings still provide a way to narrow the list.

A Substitute for Thinking?

Indeed, rankings seem to provide a shortcut of the type described by Nobelist Daniel Kahneman. He divides our thought processes into two categories: fast, intuitive, and emotional vs. logical, rational, and conscious. (See Thinking, Fast and Slow.) Kahneman notes that the human brain doesn’t like to take the difficult second path and will use whatever shortcuts it can. Rankings, and the apparent differences between listed items, seem like one such shortcut.

Whether you love them or hate them, rankings won’t go away. Use them to create more compelling content when you can, and pay attention to your own position if your product or service happens to be ranked. Indeed, you might be able to increase customer experience with a better ranking – see Use Ratings to Improve REAL Satisfaction.

And, don’t forget the key takeaway from this research: never, ever be #11!

I’m stoked to be here! I’m implementing your ideas into my advertising campaigns, and they are already helping lower my cost per click. Thanks!

[…] enticed by the headline, Top 50 Inspirations from Steve? Find out why in this item — Power of Ten: The Weird Psychology of Rankings — by Roger Dooley at Neuromarketing. Technically, I lied. Steve’s factoids aren’t […]

Interesting article. When I search for top list I usually search for top 10 🙂

Now I see there’s lots of people who do that too

[…] Power of Ten: The Weird Psychology of Rankings [Neuromarketing] […]

Great read. I knew that people loved lists, but making it easier for people to comprehend and to ‘group’ or ‘categorize’ in their minds makes a lot of sense

This is something I never would have guessed. It seems the brain and human nature always want to take the path of least resistance.