Border Bias: How to Beat It

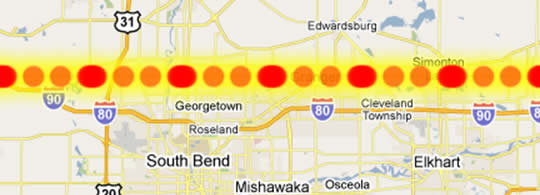

When we lived in Indiana, our first house was quite ordinary but had one feature some found a little odd: one edge of our little lot was the Michigan state line. An errant frisbee throw required one to retrieve the disc from another state. There was absolutely nothing to distinguish that lot line from any other – the border was unmarked and totally imaginary. Except as a novelty for first-time visitors, we never thought about it (at least not consciously). It turns out, though, that these imaginary lines DO have an effect on our perception of distance.

Researchers Arul Mishra and Himanshu Mishra at the University of Utah looked at how people perceive disasters, and found that if the disaster site was in a neighboring state, people felt more secure even when the absolute distance was the same. In effect, it seemed that the border either made the disaster seem more remote or provided a barrier of protection. The Mishras dubbed this effect “border bias,” noting in their paper’s abstract, “people consider locations within a state to be part of the same superordinate category but out-of-state locations to be part of a different superordinate category.”

The research was focused on disaster planning; one concern is that people might take disaster preparation less seriously if the event was nearby but in another state. But could border bias affect marketers, too?

Border Bias and Marketers

Most marketers don’t have to worry about border effects – either they are in the same geographic entity as their customers, are far enough away that one border won’t matter, or are geographically ambiguous. (Where is Amazon, anyway? I didn’t even know they had a Texas distribution center until the recent tax brouhaha.) But SOME marketers do expect customers to cross state lines, and they are the ones that need to be careful. (Service providers might also seem farther away than they really are if on the wrong side of the border.)

Another kind of border bias can kick in as well: the “us vs. them” syndrome. In some cases, geographic units may be viewed as rivals or simply looked upon negatively. As first conclusively demonstrated by Henri Tajfel, it’s all too easy for artificial distinctions to cause one group of people to discriminate against others. (See Revealed: How Steve Jobs Turns Customers into Fanatics.)

The Mishras suggest that disaster agencies avoid referring to locations by geographic unit and instead emphasize distances. I think this same advice applies to marketers. Here are a few marketing-related examples:

WRONG:

- “Southwest Michigan’s biggest Chevy dealer!” (when advertising to Indiana customers)

- “Only ten miles north of the state line!”

BETTER:

- “The area’s biggest Chevy dealer!”

- “Just 15 minutes from downtown!”

The second set of phrases will communicate the message without kicking in border bias.

Those lines may be imaginary, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t real in our minds.