Brain Scans Top Surveys

What’s more accurate than asking people to predict their behavior? According to a new study at UCLA, the answer is, “Scan their brains.” This may not come as a surprise to those engaged in neuromarketing research, but the newly published research is one step in the process of validating brain scan techniques as a market research tool capable of being more accurate than traditional methods.

“There is a very long history within psychology of people not being very good judges of what they will actually do in a future situation,” said the study’s senior author, Matthew Lieberman, a UCLA professor of psychology and of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences. “Many people ‘decide’ to do things but then don’t do them.”

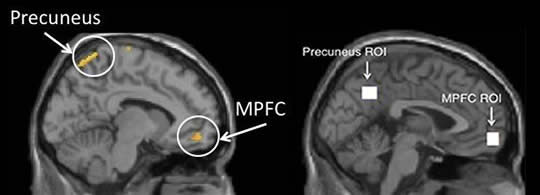

The new study by Lieberman and lead author Emily Falk, who earned her doctorate in psychology from UCLA this month, shows that increased activity in a brain region called the medial prefrontal cortex among individuals viewing and listening to public service announcement slides on the importance of using sunscreen strongly indicated that these people were more likely to increase their use of sunscreen the following week, even beyond the people’s own expectations. [From UCLA Newsroom – Neuroscientists can predict your behavior better than you can by Stuart Wolpert.]

In this experiment, subjects listened to a recorded public service announcement and viewed slides about

the importance of sunscreen. The researchers monitored their brain activity using fMRI. Remarkably, they were able to predict an increase in sunscreen use with about 75% accuracy vs. less than 50% for the subjects’ own predictions.

They began by testing ten subjects and using computer modeling to develop their predictive algorithm. Then, the researchers predicted the behavior of ten different subjects. The subjects were shuffled in different ways to build a larger data set. The work will be published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Predicting consumer behavior using traditional market research tools like surveys, focus groups, interviews, and so on has always been problematic. Sometimes people may provide answers they think the questioner will like or will make them “look good.” (Controversial candidates often get more votes than predicted by pre-election polls.) Often, though, people are just not very good at accurately describing how they might behave in the future.

We’ll never be completely successful at predicting what people will do days or weeks later, but this UCLA study suggests that looking at the activity in our brains may be significantly more accurate than what we say.