Finding a College and Choice Architecture

It’s that time of year when many U.S. high school seniors are making their final college decisions. They have their last acceptance letters, and now must choose which school they will attend in the fall. It’s a good time to think about how the college search process begins, and how the choice architecture of the college decision process can be improved.

Students in the United States are faced with a bewildering array of choices: there are nearly 4,000 colleges and universities in the U.S., and a reasonably good student can be admitted to almost all of them. (A tiny handful of very selective schools are much more difficult to enter, and account for most of the admissions angst among students and parents.) The differences between these thousands of schools are profound and multi-dimensional. The time-honored way of dealing with this plethora of choices is to create a “college list” of candidate schools, which students investigate, visit (perhaps), and apply to. The number of schools finally applied to may be quite low, say two or three, when admission is certain or nearly so, or well over ten when schools with very low acceptance rates are on the list.

Many students start from a bottom-up approach: they ignore the vast selection of options, and focus on a few schools: those with nearby campuses, the one their parents attended, the school with the big-name football team, or schools at the top of academic ranking lists. Their choice is simplified by ignoring almost all options.

Some students and parents, though, begin the process with an open mind: they may have some college ideas, but want to explore other schools that they may not be familiar with. Some of this investigation is done by personal contact: asking friends, relatives, teachers, counselors, etc., for recommendations. Social networks and online communities extend this process. Facebook, for example, extends the network to friends of friends. A community site like College Confidential (which I co-founded in 2001 and still participate in), allows interaction with many thousands of otherwise unconnected people also engaged in the college process.

Structured College Search

Some students and parents, of course, want to take a more scientific approach to college search. They want to specify criteria, like “offers marine biology as a major” or “within 200 miles” to narrow the list. This is where we get into choice architecture – how does one do this in a way that delivers the best results?

Before the Web, students pored over paper guide books to find schools that met their needs. The Web greatly simplified the process. One could create a database of information for hundreds or thousands of colleges and universities, and then let searchers specify criteria that would start eliminating vast numbers of schools. If one starts with a list of thousands, saying “get rid of everything outside California” will immediately cut the list to hundreds. Each new specification winnows the number of schools meeting all the criteria; eventually, the number is manageable.

Choice Architecture & Elimination by Aspects

The typical college search process is in essence an old algorithm dubbed “elimination by aspects” by Amos Tversky back in 1972. In short, when presented with a huge array of choices, you pick criteria which exclude many of those choices – for example distance from home, climate, and cost of attendance. As you continue, you finally arrive at a small enough set to examine in detail. This is one example of a simplifying strategy – it’s not possible to study a few thousand colleges and carefully weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each. There are a few problems with the choice architecture of even the best traditional college search tools:

- They are absolute: a school 205 miles away might be perfect in every other aspect, but if you specified a 200 mile limit you won’t see it.

- The list of acceptable choices isn’t ordered by suitability, since all meet the specified criteria.

The Solution: Prioritized Fuzzy Matching

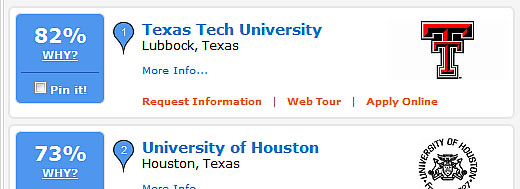

A couple of years ago, the beta version of a new tool was launched: SuperMatch™ College Search at College Confidential. (Disclosure: I was part of the team that came up with the approach, and am listed on the patent application covering some of its unique features.) The tool, more than a dozen upgrades later, has a zippy user interface, but, more importantly, produces a unique result set by incorporating the concept of fuzzy matching. In other words, choices aren’t absolute: if a student wants to go to school in Texas, but the school that is an otherwise perfect match is across the border in Oklahoma (or even in Maine), that “mismatched” school can still appear in the results.

Furthermore, the searcher can prioritize – by indicating that, say, having a major in marine biology is essential but location is of low importance, the results can be ranked by the SuperMatch algorithm to match the searcher’s preferences.

The result is that students may find the “usual suspects” on their list – the schools they had identified because they were fairly obvious choices which fit the criteria – but also some unexpected schools. A common (and welcome) form of feedback are comments like, “My top choices were in the final list, but so were a few schools I hadn’t thought of.” That’s exactly the desired effect of making the matching process a little flexible.

Nudging?

In the context of the book Nudge by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, there’s not much “libertarian paternalism” at work in SuperMatch. There’s no motivation to nudge a student searcher in any particular direction. But, if the choice architecture of the search tool adds college options for a student, there are benefits. First, it’s possible that a more suitable match for all the student’s preferences will pop up; that school might have remained undiscovered in a traditional search process. Also, adding an additional solid match to the student’s college list increases the chance of getting accepted (if some or all of the schools are highly selective) or of finding an option with a lower cost of attendance. By setting the importance of various criteria, the searcher can do some “self-nudging” by ensuring the most important priorities are weighted more heavily and schools meeting those criteria appear at the top of the list.

The cost of a college education is a huge issue in the U.S. today, as increases in tuition have greatly outpaced inflation and many students graduate with tens of thousands of dollars in debt. Adding a few additional schools to the college list might well result in a choice that reduces costs either because of lower tuition or because the student is awarded grants or scholarships.

Other Applications

Other choice processes could take a lesson from SuperMatch. I’m frustrated by travel sites that specify hard criteria, like fixed price ranges of $175 to $250 per night for a hotel. If a great choice was $255, I might be interested, but I don’t want to revise the criteria by adding every choice in the $251 to $375 range. Sliders are a better way to set a range, since at least the user can stretch the boundaries as desired to reveal a few more choices. Still, a travel search that added a bit of fuzziness to the process would produce a more satisfying result (at least for me).

The search giant Google is now celebrating fuzziness: they have just announced “near match” ads that will display ads on searches that are very similar but not structurally identical to the desired phrase.

Your Favorites?

It remains to be seen how much a tool like SuperMatch can improve the overall U.S. college choice process; it does appear to uncover surprising options for high school juniors and seniors, who usually have little free time for leisurely research. If you have experience with sorting through the maze of U.S. colleges and universities, have you found effective ways to build a college list and uncover the hidden gems among the thousands of options? Looking beyond college search, do you have a favorite site that you think does a great job of winnowing many choices (for some product or service) into a manageable number? Share your thoughts in a comment…