Honesty Research May Be… Dishonest

Dan Ariely denies involvement, Francesca Gino on leave at Harvard

Business leaders love behavioral science interventions that are simple, free, and change behavior in a significant way. Nudging people to save more for retirement by making plans opt-out rather than opt-in has helped millions of employees have a more secure future. Businesses collect all kinds of information using forms, like employment applications, market surveys, and so on… Could a simple intervention make people more honest when completing a form?

A 2012 paper showed there was indeed a simple intervention: in both lab tests and field studies, the researchers found that having people sign an honesty pledge at the top of the form caused a significant increase in honest answers. The most prominent author listed was Dan Ariely, author of the global bestseller Predictably Irrational. Ariely wrote an entire book about the topic of dishonest behavior, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, also published in 2012.

The Problem with the “Honesty” Paper

In 2020, a paper by seven authors that included the original five found that the original findings couldn’t be replicated. The new paper said, “The current paper updates the scientific record by showing that signing at the beginning is unlikely to be a simple solution for increasing honest reporting.” This paper noted that some government agencies had adopted the “sign first” approach based on the original research.

“Updating the science record” didn’t go far enough. In 2021, the original paper was retracted. after detailed analysis of its data by the blog Data Colada found “evidence of fraud.”

A report today from NPR has resurfaced this problematic research by publishing a letter from The Hartford, an insurance company. The firm provided data on about six thousand vehicles, but the published study described a data set of more than three times that number. According to an analysis by The Hartford, “…it is clear the data was manipulated inappropriately and supplemented by synthesized or fabricated data.” The letter goes on to detail why they drew that conclusion using both statistical and, oddly, typographic analysis. The apparently bogus data is in a different font than the original provided data.

Dan Ariely Disclaims Responsibility For Fabricating Data

Ariely denies being involved in any data fabrication. He told NPR, “Getting the data file was the extent of my involvement with the data.”

Ariely denies being involved in any data fabrication. He told NPR, “Getting the data file was the extent of my involvement with the data.”

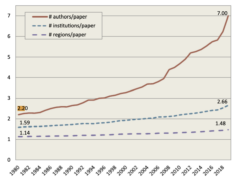

Taking Ariely at his word, this messy situation raises again the question of responsibility of listed authors on scientific papers. The paper in question has a modest number of authors – a mere five, actually below average. The average number of authors on scientific papers grew from two in 1980 to seven in 2019.

With most papers having multiple authors, what is the responsibility of each author to verify all data, methodology, etc.? Is every author responsible? Is the first author the one who assumes full responsibility? What does being listed as an author indicated about the individual contribution?

Being listed as an author on a paper for an incidental contribution is usually a good thing – publications are the lifeblood of academic success. When things go wrong, of course, being an author becomes a liability.

The Backfire Effect

At this point, Ariely likely wishes he had been listed in the original paper’s acknowledgements rather than as an author. He wasn’t the primary author, but, as the most famous name in the author list, he becomes the headline.

Nobody knows better than a behavioral scientist that denying a false claim can reinforce the belief being refuted. The more traction the story gets, the more Ariely’s reputation can become tarnished – even if he had nothing to do with the apparently fabricated data.

Replication in Behavioral Science

This questionable paper is part of a much larger issue in the social sciences: studies often find significant effects for interventions, but other researchers are unable to replicate them. This has been dubbed “The Replication Crisis” by some.

I spoke with Ariely about this topic in 2017. He downplayed the “crisis” concept, noting that many attempts to replicate studies vary in some important way from the original research. The subjects differ in things like age, geography, culture, and other demographic factors. Research methodology and sample size can differ. Differing results are to be expected when the replication isn’t identical.

Ariely said the welcomed replication studies, particularly those that attempt to expand the learning from the original research, such as identifying conditions would make the result stronger or weaker.

Ariely also urged caution on accepting the results of one study:

You see one experiment, don’t get convinced. No matter what the experiment is, don’t be convinced 100%. Change your belief a little bit in the direction of the data.

Some replication problems, of course, come from bad research. Under pressure to publish important findings, researchers can torture the data they collect until something significant emerges. Outlying data points can be discarded as errors to produce a stronger result. Conclusions based on a small number of subjects can be expressed as a general understanding of human behavior.

Less common is wholesale fabrication of large data sets as is claimed to have happened here.

Bad News for Behavioral Science

In the case of the “signature at top” paper, the problem may lie, at least in part, with co-author Francesca Gino, a behavioral scientist at Harvard Business School. Last month,the Data Colada bloggers say they found evidence of fraud in four of her papers. Her status at Harvard is currently “on administrative leave.”

Issues like this one and the downfall of Cornell’s Brian Wansink damage all of us who try to apply behavioral science to real problems in business and government. When we cite studies that show an intervention works, will organizations believe us? Should we ourselves believe the research?

The answer, at least for now, echoes Dan Ariely’s comment about not putting too much faith in one study. Instead, we should focus on science that has been broadly replicated both in both academic and business environments many times over. There’s no doubt at all that concepts like Cialdini’s social proof and authority can influence behavior – digital marketers have millions of data points that back up the science. There is real behavioral science.

Even then, in business we need to exercise the same caution Ariely recommends for replication: every target audience is different, and the same results won’t be achieved every time.