Some Learn From Mistakes, Others Don’t

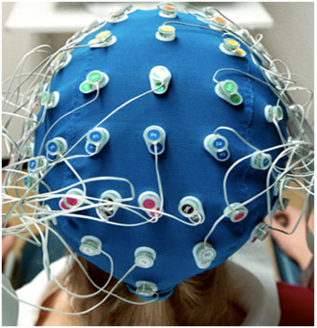

In Managing by Mistakes, I wrote about the power of learning from mistakes. Some of the most successful individuals in different fields credit relentless focus on even small mistakes with their high achievement. Researchers at Columbia University divided student subjects into two groups, “grade hungry” and “knowledge hungry” based on a short survey, reports Newsweek’s NurtureShock column, and then tested them with general knowledge questions. The researchers immediately provided feedback as to whether the subject was right or wrong, and showed the correct answer. The brain activity of the subjects was monitored using EEG caps. The differences in the way the subjects handled the feedback was striking:

In Managing by Mistakes, I wrote about the power of learning from mistakes. Some of the most successful individuals in different fields credit relentless focus on even small mistakes with their high achievement. Researchers at Columbia University divided student subjects into two groups, “grade hungry” and “knowledge hungry” based on a short survey, reports Newsweek’s NurtureShock column, and then tested them with general knowledge questions. The researchers immediately provided feedback as to whether the subject was right or wrong, and showed the correct answer. The brain activity of the subjects was monitored using EEG caps. The differences in the way the subjects handled the feedback was striking:

The Knowledge-Hungry paid attention (but not quite as obsessively) to whether they were right or wrong, and they paid significantly more attention to the correct answers. They took advantage of the chance to learn. This contrast was most dramatic when each group got an answer wrong. The Knowledge-Hungry activated deep memory regions, indicating they were storing these new facts away for later. Such activity was not nearly as deep in the Grade-Hungry, suggesting a far more cursory interest; instead, their brains seemed to feel threatened by learning they’d gotten an answer wrong. Their brains indicated a far more emotional, fearful response. They clearly did not like being wrong, and they didn’t care that Katmandu is in Nepal.

Not surprisingly, when the students were later surprised by a retest, consisting only of the questions they’d gotten wrong the first time around, the Knowledge-Hungry kids did far better. [Emphasis added. From Newsweek NurtureShock – This is Your Brain on a Test by Po Bronson.]

So, from a neuromanagement viewpoint, it would make a lot of sense to hire people capable of learning from their mistakes. Hiring the equivalent of the “grade hungry” students will yield employees who are motivated but who, over time, may not improve their performance nearly as much as individuals who internalize lessons learned when things don’t work perfectly.

So how can you screen for this trait of learning from mistakes? The researchers asked the students questions about their motivation:

One group was concerned, primarily, with being better than others. They agreed with statements like, “You have a certain amount of intelligence and you can’t do much to change it,” or “It’s important to me to be smarter than other students.” The other group disagreed with those statements, and instead agreed to comments like, “It’s very important to me that my coursework offer real challenges.” This latter group wasn’t into comparing themselves.

Clearly, the second group might well make better employees (although the motivation for doing better than one’s peers shouldn’t be discounted). Via either testing or the interview process, teasing out the “learners” should be possible. (The hiring process in the U.S. is governed by a variety of laws and agencies, so be sure to check with a human resources professional before subjecting applicants to a test of your own design!)

The Columbia University research was led by Carol Dweck, whose work was also featured in our article, How to Praise Your Child.