Our Prejudiced Brains

Years ago, I worked with a group of field representatives selling industrial equipment, and found that many had interesting adaptations to local culture in different parts of the U.S. One based in Texas always kept a Western-cut sheepskin jacket in his car. If he was visiting a plant in a remote location, he’d shed the suit coat he wore in Dallas and put on the rugged-looking jacket. The reps in Detroit, meanwhile, were always careful to show up in the appropriate brand of vehicle – one wouldn’t take a Ford engineer to lunch in a Chevy! While these strategies of blending in may seem obvious, it turns out there’s some sound neuromarketing involved.

Years ago, I worked with a group of field representatives selling industrial equipment, and found that many had interesting adaptations to local culture in different parts of the U.S. One based in Texas always kept a Western-cut sheepskin jacket in his car. If he was visiting a plant in a remote location, he’d shed the suit coat he wore in Dallas and put on the rugged-looking jacket. The reps in Detroit, meanwhile, were always careful to show up in the appropriate brand of vehicle – one wouldn’t take a Ford engineer to lunch in a Chevy! While these strategies of blending in may seem obvious, it turns out there’s some sound neuromarketing involved.

Harvard researchers have found evidence that our brains react to people differently depending on our beliefs about them and whether we perceive that they are “like us.” While obvious external clues like race and sex can trigger the different reactions, even what we believe to be true can have that effect.

The authors detailed the function of a particularly important brain area while studying the neural correlates of “mentalizing.” Mentalizing is the ability to predict how other people will behave in a given situation. It combines the powers of theory of mind (our ideas about what other people know and do not know) with the presumptions that we hold about people with dissimilar backgrounds. Some researchers believe that mentalizing is a function of the brain’s mirror neuron system, allowing us to predict the behavior of others by simulating how other people may feel in a given situation. [From Scientific American Mind Matters – How Harvard students perceive rednecks: The neural basis for prejudice

The researchers found that subjects reacted differently to profiles of individuals thought to be either fundamentalist Christians from the Midwest or liberal northeastern students depending on their own beliefs. In fact, the profiles were randomly assigned to photos culled from a dating service. The subjects themselves were surveyed and put in conservative and liberal categories.

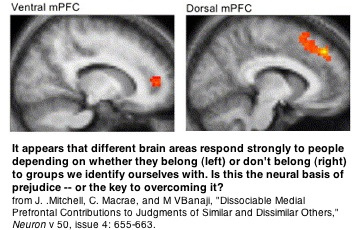

Prior research had suggested that the medial prefrontal cortex, or mPFC, an area stretching up and forward from roughly beneath the temple, was known to be involved in mentalizing. The researchers hoped to distinguish whether two important parts of the medial PFC, the ventral mPFC (toward the front of the mPFC) and the dorsal mPFC (further toward the top of the head), might be reacting differently. The brain imaging results indeed indeed showed a dissociation between these two regions. Heightened activity in the ventral mPFC was associated with mentalization of self-similar people, whereas dorsal mPFC activity was associated with mentalization of self-dissimilar people.

In plain English, the subjects’ brains showed different kinds of activation when viewing individuals they thought were similar vs. individuals thought to be different. There was a bit of good news – the differences in brain activation were minimal when the subjects imagined the profiled individuals engaged in a neutral activity, like enjoying Thanksgiving with family.

The marketing takeaway is that people will categorize others as being similar or dissimilar based on both external cues like appearance as well as what they believe to be true about the individual. So, when the salesperson walks into a customer’s office and says, “Hey, I see you are a Notre Dame football fan too! What do you think they’ll do next season?” he is doing more than breaking the ice with the customer. He’s at least moving to neutral ground and at best establishing himself as “like me” in the customer’s mind.

Advertisers need to think about this issue too – a spokesperson who falls into the “one of us” category may prove to be more believable than one who seems dissimilar. No doubt this is one reason why Peyton Manning’s “guy next door” appearance and demeanor are more popular with advertisers than, say, a long-haired, hulking lineman covered with tattoos.

For those interested in reducing prejudice in society, the research confirms the advice that emphasizing areas of shared similarity is one important way to get individuals to identify with others who may look different or espouse other beliefs.