When Consumption Isn’t Conspicuous

Marketers know that a key element in many purchases is to signal something about the buyer. A Toyota Prius, for example, says that its owner is concerned about the environment. Expensive luxury brands let the world know the buyer has discriminating taste, and, more importantly, has plenty of money. Whether you believe in the evolutionary psychology explanation (“Look at me, I have excess resources, I would be a great mating choice!”) or simply feel some people need to show off, you likely agree that the signaling aspects of luxury products are a key factor in the success of those products. Indeed, in The Luxury Strategy, Kapferer and Bastien suggest that many luxury brands advertise not to attract customers but to be sure that the rest of the population can identify these brands when their wealthy users display them.

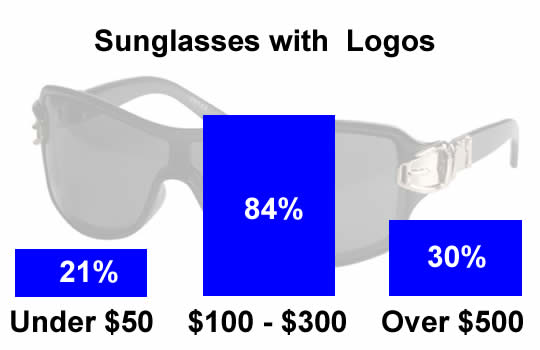

In the context of this need for conspicuous consumption, recent research may surprise some: at the higher end of the market, the more expensive an item is, the less likely it is to include a logo or name:

“Consumers often spend lavishly to communicate wealth and status to those around them and explicit branding facilitates this process,” write authors Jonah Berger (Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania) and Morgan Ward (Southern Methodist University). “Handbags with Gucci written across them in large letters, or ties covered in Burberry plaid make it easy for observers to know what brand someone purchased and that they had money to burn.”

But many high-end products do not display brand names or logos. In an analysis of handbags and sunglasses, the authors found that while only 21 percent of sunglasses under $50 contained a brand name or logo, this increased to 84 percent among sunglasses that cost between $100 and $300. However, among sunglasses priced above $500, only 30 percent displayed their brand. [From the Journal of Consumer Research – Inconspicuous Consumption: Insiders vs. Outsiders.]

The authors think the real signaling value of these inconspicuous luxury items is not directed at the general population, who likely won’t recognize them, but at “insiders” who will, e.g., one’s wealthy peers.

Overall, my takeaway from this study is that marketers need to be careful with logo strategies, particularly for luxury items. While success in one segment of the market demands a distinctive, recognized logo on the product, as one moves up the price ladder removing the logo and using more subtle design cues may be necessary.

One strategy I find rather odd is Ralph Lauren’s addition of huge Polo logos to some of their shirts; while these emblems are a potent signaling device due to their size, they strike me as nearly a parody of luxury symbology. Perhaps it’s smart, though. Ralph Lauren’s Polo brand is widely distributed and is positioned in the premium (but not ultra-premium or true luxury) segment where logo signaling is important.

Note that very high end customers may be even more brand conscious than other segments, but they seek to signal their affluence in a more subtle way. To that end, branding efforts should go well beyond the logo and products should share other characteristics. Colors, materials, unique design elements, etc. can all fill this role. Branding is still of prime importance, but its manifestation is different.